INTRODUCTION

In June 2019, the European Union (EU) and Mercosur reached a preliminary agreement to establish a strategic partnership. This partnership was structured around three main pillars: trade and commerce, political dialogue, and cooperation and development aid. These elements exemplify what has been called the fourth generation of EU agreements (Trein & Cavalcanti, 2007; Caballero, 2022). Politically and economically, the deal carried significant weight. On the political side, the agreement was viewed as a countermeasure to the rising tide of protectionism, which had been fueled by escalating tensions between China and the United States (US) (Álvarez & Zelicovich, 2020; Rodríguez & Sanahúja, 2019). From an economic perspective, the trade deal was notable for two key reasons. First, it aimed to establish one of the world’s largest free trade areas, encompassing nearly 800 million people and a quarter of the global GDP. Second, the agreement's commercial provisions were comprehensive, covering sanitary and phytosanitary measures (SPS), technical barriers to trade (TBT), the liberalization of services and investment, access to government procurement, intellectual property rights, and other areas.

The negotiations for the agreement, nonetheless, started 20 years before, in 1999. Given the contrast of both blocs’ economies and commercial interests, the most troublesome pillar of the negotiations was inevitably the commercial one, being the main responsible for the slow movement of the whole process.

In any case, the period from 1999 to 2019 does not represent a continuous process of trade negotiations. Indeed, the negotiations that started in 1999 reached an impasse in October 2004, when the deadline for achieving a deal was attained without a satisfactory conclusion for the sides. The deadline for the conclusion of the trade talks was established by the 2003 Brussels Work Program and coincided with the end of the Prodi Commission, which had been granted the mandate for the negotiations (Arana, 2017). From 2005 to 2010, there was a hiatus in the negotiations, with some minor intents of resuming talks (Araújo, 2018).

With the failure to achieve a deal at the multilateral level and the constant economic growth of the of Mercosur members, the interest to resume negotiations became more apparent on both sides of the Atlantic. Finally, in 2010, under the Argentinian pro-tempore presidency of Mercosur, the negotiations were resumed, but under a whole new different logic. While in the first negotiation phase (1999-2004), the European fear of losing markets for the US – which was negotiating the FTAA with Mercosur under the “4+1” framework – predominated, during the phase inaugurated in 2010, the EU operated under a less defensive logic, seeking to expand its market in countries that were constantly growing, stimulated by the commodity boom. In Mercosur, the logic was also different given the exhaustion of the multilateral trade talks and the intensification of the interventionist agenda in its leading member states, Brazil and Argentina.

While the early phase of the trade negotiations has been covered by academic works, such as Savini (2001), Ventura (2005), and Araújo (2018), more recent works tried to comprehend the whole negotiation process, embracing its twenty-year duration (Álvarez & Zelicovich, 2020; Rodríguez & Sanahúja, 2019). With this article, we aim to concentrate on the second phase of the trade negotiations between Mercosur and the EU, emphasizing the perspectives of the South American bloc’s leading economies, Brazil and Argentina. Indeed, we envisage looking at the position of both countries vis-à-vis the negotiations with the EU through the lens of foreign policy analysis that observe interrelation of international insertion strategies and development models.

Therefore, besides this short introduction, this work is subdivided into four sections. Firstly, we will comment on the theoretical framework that will underpin our analysis. We propose to view the relaunch of the negotiations in two subperiods. On the one hand, from 2010-2015, the negotiations just focused on normative and regulatory terms, with no further advancements in terms of offer exchanges. During that phase, Brazilian and Argentinian government developed internally and externally their neo-developmentalist agenda, which enforced their defensive posture in the talks with the EU. On the other hand, from 2016-2019, with the inauguration of new-right governments in both countries, the liberalizing program was enforced internally and externally, leading Brazil and Argentina to less resistant on both countries’ defensive interests (e.g. Intellectual property, industrial goods, public procurement) and less demanding on their offensive interests (e.g. Agriculture). Indeed, to conclude the negotiations, both countries ceded on some of its historic positions (Ferro, 2024). The periods of 2010-2015 and 2016-2019 will be the topic of sections two and three, respectively. Lastly, we will develop a short conclusion.

DEVELOPMENT

Theoretical framework

Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) function as both foreign policy and economic policy tools, influencing not only domestic economies but also international relationships. Economic openness through trade deals can create "asymmetrical benefits," boosting certain sectors while harming others (Soares de Lima 2000). This dual role makes it essential to examine the connection between foreign policy and a government’s economic agenda, especially in analyzing trade negotiations like those between Brazil, Argentina, and the European Union (EU).

Table 1. Variables of the three dimensions of a development model

Productive Dimension |

Financial dimension |

Social dimension |

1a. Productive structure |

2a. exchange rate policy |

3a. income distribution |

1b. external opening |

2b. interest rate |

3b. poverty reduction/ employment creation |

1c. Trade policy and instruments |

2c. inflation rate |

3c. Education and Health |

1d. FDI criteria |

2d. domestic savings |

3d. R&D Promotion |

2e. relation internal/ external funding |

3e. Infrastructure |

- Based on Actis, Lorenzini and Zelicovich (2016)

To explore this, Actis, Lorenzini, and Zelicovich’s (2016) framework for Foreign Policy Analysis (FPA) is adopted. This approach links development models – understood as a strategy of articulating the state and the market for the transformation of a country’s productive and social structures – with international insertion strategies – understood as how a country positions itself in the global system. Development models are broken down into three dimensions: productive, financial, and social. These dictate, for instance, how a country integrates its production system with global markets, manages its exchange rate and fiscal policies, and addresses wealth distribution and social welfare. The variables to be analyzed in each of the dimensions of a development model are displayed in Table 1.

Development models fall into three categories: liberal, developmentalist, and neo-developmentalist. Liberal models emphasize free-market policies, minimal state intervention, and global integration. Developmentalist models prioritize state-led economic growth and protectionism, while neo-developmentalism blends both, promoting selective global engagement while safeguarding against financial instability.

Each of these models tends to align with specific international strategies, as displayed in table 2. A liberal model often leads to a globalist strategy, seeking full adherence to the international order for economic gains (Escudé, 1995). A developmentalist model leans toward a strategy of impugnation, challenging the global system to protect national interests. Neo-developmentalism favors reforming the system from within, balancing autonomy with global engagement.

As these are just ideal types, our analysis will be guided by these references, but they shall not be always found in empirical terms. In other words, both the development models and international insertion strategies mentioned above will be treated as a continuum in our analysis. Therefore, a development model can be more liberal or developmentist-oriented, not perfectly aligning with an ideal type. The same is valid for the international insertion strategies, which makes the use of this framework even mre interesting.

Table 2. axis of articulation between international insertion strategy and development model

Dev. Model/strategy |

Globalist strategy |

Strategy of impugnation of international order (autonomy logic) |

Strategy of reform of international order |

1. Productive dimension |

External openness (unilateral or open regionalism) |

North-South logic. Closed Regionalism |

Selective and strategic connection |

2, Financial dimension |

Openness for foreign capitals |

National Financial control (to avoid external vulnerability) |

Creation of alternative spaces in the South-South axis |

3. Social dimension |

Spillover effect guided by market-drive economy |

Positive effects of closed regional integration and cooperation North-South |

Widening of regional integration agenda (energy, environment, productive integration) |

- Based on Actis, Lorenzini, and Zelicovich (2016).

A slow restart: the relaunch of the negotiations between the EU and Mercosur (2010-2015)

Following the stalemate of the negotiations at the WTO level, the actions to promote a relaunch of the bi-lateral talks started to take form. In a bi-lateral meeting between Brazilian and Spanish representatives, Brazilian chancellor Celso Amorim, accompanied by his Spanish counterpart Miguel Angel Moratinos, argued that “the uncertainties surrounding Doha [round] led us to pursue the EU-Mercosur agreement with greater commitment. Let's concentrate our efforts [in it]” (FSP 07/31/2009)2. The Commission’s president, João Manuel Durão Barroso (2004-2014), stated that one of the goals of the the 3rd Brazil-EU Summit, which took place in Stockholm in October 2009, was to articulate a way out of the hiatus (FSP 10/05/2009). In the occasion, both Brazilian and European representatives said that the next Spanish Presidency of the European Council was a great opportunity to resume talks (FSP 10/05/2009). The final declaration of the 3rd Brazil-EU Summit clearly stated that both sides “agreed to intensify their work towards the resumption of negotiations with a view to conclude an ambitious and balanced EU-Mercosur Association Agreement” (Brazil & European Union, 2009, p. 6).

Finally, in May 2010, the talks were finally resumed with a new meeting of the Bilateral Negotiations Committee on the 4th. On the European Side, the logic of the new period of the negotiations was different from the 1999-2004 phase: instead of having the defensive interest of securing a market that could fall in the hands of the United States via the FTAA, the EU had instead an offensive interest in Mercosur given its rapid and expressive growth rates in the 2000s and the challenging scenario the EU faced after the 2008 crisis (Filho, 2018). On Mercosur’s side, especially in Brazil and Argentina, given the continuation and deepening of the neo-developmentist traits in their development models, the logic was close to the one of the 2003-2004 period: conclude a deal with the EU that was “ambitious” but with as little interference as possible in both governments' autonomy to carry out industrial policies, given their aim of changing the productive structures of their countries and privileging the creation of comparative advantages.

In Argentina, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner’s endeavors did not only follow her predecessor’s neo-developmentalist model but also tried to continue it under a scenario of growing economic constraints. After the 2008, commodity prices fell, affecting Argentinian GDP – which fell by 6% in 2009 –, internal market, employment levels and manufacturing production. Following the state-led economic approach she always defended to avoid a worse scenario for the Argentinian economy, the President proceeded to anti-cyclical measures. Therefore, her government not only tried to maintain the fiscal subsidies, high public expenditure, and the macroeconomic guidelines of the her predecessor (low interest rate and competitive fixed exchange rates) for the continuation of the re-industrialization effort – aiming to keep to the productive and the financial dimension of her predecessor’s development model –, it increased the state’s presence in the economic activity by renationalizing some companies (ex. Re-gaining the control of YPF from Repsol in 2012) and by promoting welfare measures to tackle the harmful effects of the international crisis. In other words, CFK deepened the state’s role in the social dimension of the development model. Her government augmented wages and pensions, increased government spending on public works, created new social benefits – such as the Universal allocation per Child and the Universal Pregnancy Allowance – and, most importantly, re-nationalized the entire pension system (Belini and Korol, 2020).

Most of the recovery package was maintained by primary monetary issue (Rapoport, 2017). In the end, the expansive range of the fiscal and monetary policies promoted by the government led to an economic recovery at the price of expressive inflationary growth and fiscal imbalances. The fiscal needs of the country pushed the government to re-open the negotiations with the Paris Club to find a solution for the creditors that were not included in the 2005 debt renegotiation. In 2010, the government could finally strike a deal with 93% of the creditors (Belini and Korol, 2020) – overcoming the 73% achieved in 2005 –, but at the price of using national reserves for paying private creditors and financial organizations, which contradictorily left Argentina in a very uncertain financial position.

In summary, CFK tried to continue and even expand her predecessor’s neo-developmentalist model, but the rougher economic scenario led the government to fragilize one of the key aspects of the model’s financial dimension: the maintenance of constant twin surpluses (fiscal and external). Both served as an instrument to maintain financial sustainability of the re-industrialization. Given the governments difficulties to promote fiscal adjustments and save foreign reserves (Musacchio, 2015), this inevitably led to an inconsistency inside the Argentinian development model (Actis, Lorenzini, & Zelicovich, 2017).

In Brazil, Lula’s final years in office were more ambitious in trying to promote a re-industrialization of the country. With the ascension of his successor, Dilma Rousseff (2011-2016), these policies became even more apparent. Under the effects of the European debt crisis, President Rousseff also promoted an anti-cyclical package – popularly known as “the new economic matrix” – that intensified the neo-developmentist character of the Brazilian model. In 2011 and 2012, Lula’s successor expanded pro-manufacturing policies by: promoting tax breaks for 15 labor-intensive sectors; expanding credit for enterprises via the Brazilian development bank (BNDES); the launching of the public investment called “Brasil Maior”; implementing a whole package of measures to stimulate national production, including rises in taxes for imported vehicles that used less than 65% of national components and the use of Petrobras and government procurements program to foster national production of equipment, vehicles and medication; altering contracts with energy concessionary companies for cheapening energy prices (Singer, 2015).

Most importantly, another part of the anti-cyclical package was to introduce policies that broke up with the macroeconomic tripod (primary fiscal surpluses, floating exchange rate and inflation target regime), which represented the first clear attempt to alter the financial dimension of the Brazilian development model since the macroeconomic tripod was established by Cardoso’s government in 1999. Although Lula’s terms progressively carried out a shift from a more liberal development model to one more with more neo-developmentalist traits, as we previously discussed (Ferro, 2024), his macroeconomic policy framework was still the one inherited from Cardoso’s second term – still aiming to attract credibility and promote stability above all. The continuation of the macroeconomic tripod was an obstacle to Lula’s reindustrialization efforts and neo-developmentalist intentions (Cano & Silva, 2010; Bresser-Pereira, 2013). In this sense, President Rousseff tried to consolidate the neo-developmentist orientation of the Brazilian development model by attacking the last dimension in which liberal guidelines prevailed.

On the one hand, Rousseff’s presidency attacked the monetary leg of the tripod. Under the new president of the Brazilian Central Bank, Alexandre Tombini, appointed by Rousseff, the institution instead of raising interest rates under the context of the European crisis decided to lower progressively the annual interest rate from 12,5% in August 2011 to 7,50 in April 2013. As observes Singer (2015), it was the lowest point it achieved since 1986 and, considering the interannual inflation in the period of 6,59 %, the real interest rate was below the 1% margin. Consequently, from having a very orthodox handling of the inflationary target system, whose aim was to inspire credibility and stability, Brazil started to have a monetary policy that wanted to favor credit, consumption, and above all productive investment. On the other hand, her presidency also tackled the exchange rate leg of the macroeconomic tripod. From February to May 2012, the central bank acted to devaluate the Brazilian currency from 1,65 per dolar to 2,02 per dolar, a drop by 19,52% (Singer, 2015). Such move envisaged to bolster national production and deepen the import substitution endeavors (Bresser-Pereira, 2013).

Given this scenario, although there was renewed interested in both sides of the Atlantic for a trade deal, with re-industrialization at the center of the Brazilian and Argentinian governments – and consequently the necessity of national autonomy for conceiving and implementing it –, it was very difficult for Mercosur to proceed to the consolidation of joint offers. Not even the exclusion of Venezuela from the talks with the EU – as it was still in the process of adapting to the customs unions norms and compromised to accept whatever was negotiated– was an impulse for a common Mercosur proposal. From 2010 to 2012, there were 10 meetings of the Bilateral Negotiations Committee (BNC) with no substantial developments.

Mercosur kept a strategy that rather focused on the normative aspects of the deal and, as BID-INTAL (2011) characterized, there were advances only in the regulatory and normative texts from the 16th to 22nd BNC (2010-2012). Regardless the commercial volume of the bloc’s exports to the EU, which represented 19,5% of its total exports, and 17,1% of the Argentinian and 21,5% of Brazilian exports, respectively, (BID-INTAL, 2011), both governments maintained a very though posture regarding their offensive interests (especially agriculture) whilst they remained not much flexible in terms of access to services, investment, above all, public procurement and property rights. Commitments in such areas could affect national governments’ policy space to promote industrial and development policies. Therefore, Mercosur’s bargaining margin with the EU continued to be small and maintaining a normative approach could work as a time-sparer.

Indeed, in line with the Argentinian and Brazilian neo-developmentist agenda and the required national autonomy to consolidate it, the conditionalities that Mercosur had for the negotiations post-relaunch were several. Most of them were centered around the demand to establish the trade pillar of the Association Agreement around the Differential and Special Treatment (DST) – repeating the demand for “asymmetric reciprocity” made at the first phase of the negotiations, from 1999-2004 (Araújo, 2018; Ferro, 2024). Such principle – and legal device inscribed in the 1979’s GATT “enabling clause”– provides different treatment for developing countries in FTAs with the developed world. Using the DST as a shield, Mercosur demanded: 1. Longer delays for its trade liberalization schedule, sometimes exceeding ten years (time asked by the EU) and even with extra grace years to adapt for complete liberalization; 2. smaller trade liberalization on its side, which would achieve at least 87% of imported goods from the EU (as it was in September 2004 offer) but could be less than 90% (demanded and offered by the EU in its September 2004 proposal); 3. The GSP (General System of Preferences) to be used as a base tariff for the EU’s liberalization offer instead of the Most Favored Nation (MFN) tariff – being the former more reduced than the former; 4. Commitment to a liberalization offer on the EU side that could surpass the 90% of Mercosur exports to the European bloc, improving the 2004 offer; 5. Quotas for agricultural products that could really represent Mercosur’s exporting potential with (a) zero in-quota tariff, annual (b) increases for each quota, and that the quota should be managed by the exporter; 6. A guarantee that the EU would not use subsidies for the goods exported to Mercosur or a mechanism that annulate the effects of EU’s internal measures for goods exported to Mercosur; 7. An infant industry clause and differentiated rules of origin (BID-INTAL, 2014).

Notwithstanding, to see what could be given to Mercosur, in late-2012, the EU decided that it no longer could discuss without an offer on the table. In October 2012, at the 25th BNC meeting, the EU recognized the limitations of normative-focus approach and pressured Mercosur for presenting an offer on market access, services, investment, and public procurement. The final declaration of the meeting clearly stated that “the EU underlined that it was now necessary to move to the exchange of market access offers on goods, services and investment, and government procurement”, while Mercosur, to advance negotiations, required a ministerial-level meeting (BNC, 2012). Both parties agreed on a bi-regional ministerial-level meeting to occur marginally to the 1st EU-CELAC Heads of State and Government in Santiago in April 2013.

At this point, it is important to observe that the positions about a trade deal inside Mercosur’s leading economies were not entirely convergent. While Brazil and Argentina shared a similar neo-developmentist direction under Rousseff and CFK and both shared the same negative agenda regarding the trade negotiations (with both not much flexible in terms of the themes wished by the EU, such as equal access to public procurement and property rights), the former was more interested in negotiating with EU – and slightly more flexible to its demands. In this sense, the final declaration of the 4th Brazil-EU Summit clearly stressed that “the continued advancement of the negotiation process [with the EU] requires, at this point, the discussion of preferential access to their respective markets, including the exchange of market access offers” (Brazil & EU, 2013).

Three reasons can be appointed for Brazil’s more openness for negotiating with the EU. Firstly, geopolitically, the agreement would be important for Rousseff’s autonomic insertion strategy with a universalist vocation (Lessa & Cervo, 2014). Continuing Lula and Amorim’s foreign policy, which had as a goal to transform Brazil not only into a regional focus of power but also a global actor that could be the intermediary between North-South, the agreement would consolidate the links with the EU – that were already enforced since the 2007 strategic partnership – and strengthen Brazil’s position as interlocutor for South America in a multipolar world order. Secondly, internally, the most important veto players for the negotiations changed their position regarding the agreement. Seeing negotiations of the so-called “mega regional trade agreements”, such as the TTIP3 and RCEP4, major Brazilian industrial associations, namely FIESP and CNI, became largely in favor of a trade agreement with the EU in 2012-2013 (Araújo, 2022; Berringer & Forlini, 2018; Singer, 2015; Pose, 2022).

Finally, the economic constraints faced by the Brazilian government were not nearly as intense as the ones faced by the Argentinian government – whose fiscal and external constraints became stronger from 2012 on (Belini & Korol, 2020; Musacchio, 2015). On the one hand, Brazil had more comfortable external situation as the country had paid off all the debts with the IMF in 2006 (IMF, 2024), which allowed a constant growth of its foreign reserves since then (World Bank, 2024). On the other hand, Rousseff tried to avoid fiscal concerns especially since 2013, when her neo-developmentist bid was slowed down. After the 2013 June street protests in Brazil, the President promised expressive expenditure cuts (Singer, 2015).

In any case, at the ministerial-level that took place marginally to the 1st EU-CELAC Summit, Mercosur’s representatives decided that the next BNC meeting would just take place when both sides had their offers. The deadline for presenting an offer on access for goods, services, investments, and public procurement would be primarily the end of 2013 (Filho, 2018).

From 2013 to 2014, the negotiations went into a pause as the challenge was to conform a joint offer despite Argentinian government’s resistance. While Uruguay and Paraguay were ready for exchanging offers and concluding a deal as soon as possible (BID-INTAL, 2014) – as they always had been –, welcoming the Brazilian openness to conform a common offer, Argentina’s resilient position continued to isolate the country in the bloc (Filho, 2018). Still at the end of 2012, when the EU let clear that the negotiations could not go any further without exchanging offers, Argentina was still struggling to define a national liberalization offer and wanted to continue pressing the EU for a clear definition of the conditions before the offers (BID-INTAL, 2014).

The challenge was to conform to a common offer that was considered reasonable, achieving a liberalization of at least 87% of the EU imports – which was the last offer the Southern bloc made to the EU in 2004. It was expected that the four countries presented its offers at a Mercosur ministerial meeting on October 30th in Caracas (OESP 11/10/2013)5, but Argentina did not present it by the end of 2013.

The new deadline for Argentina was March 7th, 2014 (OESP, 02/26/2014). When Argentina’s offer was disclosed – after reports that Brazil implicitly threatened of activating the possibility of liberalization by national (and not common) lists for a second time6-, Mercosur’s offer did not reach the 87% target (OESP 05/01/2014). While it was decisive to have larger liberalization margin by Mercosur’s leading economies, as they account for majority of the bloc’s external trade, Argentina’s offer just attained 76% of its imports from the EU. As Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay offered respectively a liberalization of 88%, 95% and 92% of their EU imports, the final offer represented just 82% of the trade with the EU (05/28/2014).

Finally, at the Common Market Group Summit in Caracas, on July 29th, the Heads of States of Mercosur member states publicly announced they had achieved a final common offer (Mercosur, 2014). Notwithstanding, the EU, probably expecting that no deal would be reached within Mercosur, did not have a common offer (Filho, 2018). Moreover, the conclusion of Mercosur’s common proposal occurred during the European Summer vacation and not far from the European elections, scheduled for October.

In this sense, a meeting between the EU and Mercosur’s representatives only took place under the new Commission at the 2nd EU-CELAC Summit in June 2015. At the occasion, the EU delegation and Mercosur’ foreign ministers agreed on an offer exchange. Nonetheless, to verify if the offer would subscribe to the principles established by the relaunch of the negotiations (e.g. Better offers than the ones previously presented in 2004), the EU demanded a technical meeting, which took place in Asunción in October 2015. After the Asunción technical encounter, both parties agreed to proceed to exchange offer in May 2016 (BID-INTAL, 2015).

The acceleration and conclusion of the negotiations (2016-2019)

The new governments in Brazil and Argentina decisively sped up the negotiation process with the EU. Presidents Mauricio Macri (2015-2019), in Argentina, and Michel Temer (2016-2019), in Brazil, were precisely affiliated to liberalism ideologically. Nonetheless, their liberalism manifested itself not only in their rhetoric but also in their development models and international insertion strategies. Indeed, the liberal shift increased the speed and intensity of the negotiations and largely contributed to their conclusion as Mercosur became clearly more flexible for EU’s offensive interests (especially, public procurement and property rights). This flexibility is mainly due to the new governments’ vision of their predecessors’ economic agenda as a failure. Therefore, national autonomy to design and implement industrial policies that could change the national production structure was not considered desirable or necessary. Grosso modo, both governments’ aim was to insert their countries as much as possible in the globalized economy.

Indeed, both Macri and Temer adopted measures to adapt their countries development models vis-à-vis the liberal principles. Once again – but in a very different international context – the triad de-regulation, de-bureaucratization, and destatization would again be the fundamental guidelines for economic policymaking. Stability and credibility would be mantra endorsed by both governments. Acquiescence to financial and commercial globalization would pave the way to sustained economic growth. Nonetheless, it is relevant to verify that the national economies that they were trying to re-order under the liberal receipt were different.

Argentina was facing from two different constraints (external and fiscal), while it was undergoing an inflationary acceleration that reached approximately 40.5% in 2016 (ECLAC, 2018). To tackle three problems at once, Macri’s government proposed the traditional liberal reforms. In the productive dimension, shifting the focus of the previous government in building competitive advantages in manufacturing, his administration clearly wanted to consolidate Argentina’s position as an outstanding producer of primary goods in the world. With this purpose, by 2017 his government abolished most of the export tariffs for the agricultural, livestock and mineral goods and reduced by 5% the tariff on soybean and its derivatives (Palmisano and Teubal, 2020). Seeking to attract foreign investments flows that were supposedly repressed, his government wanted to stabilize, reorganize, and open the Argentinian economy. This implied also changing the financial dimension of the development model. First, to tackle inflation, Macri established a traditional orthodox inflation targeting system from 2016-2018 – which was later replaced by a system of controlling monetary aggregates. Simultaneously, he let the exchange rate fluctuate and abolished the exchange rate controls to unify the national exchange rate – as Argentina had multiple exchanges rates due to the exchange rate controls (“cepo cambiario”) established by CFK in 2012. Finally, in 2017, weaking the capital controls, he eliminated the deadline of 120 days for foreign capitals to stay in the country – established to avoid carry trade (Actis and Zelicovich, 2019).

Also to re-establish Argentina in the world as possible financial destination and make amends with the international financial system, Macri’s fiscal policy guided the by the austerity principle, which implied especially huge changes in the social dimension of the development. His administration promoted large tax cuts by periodically withdrawing subventions from electricity, gas, water, and public transportation and promoting multiple layoffs to diminish the public spending with personnel. Moreover, to complement the austere character of his fiscal policy, Macri never implemented real increases in the minimum wage, social allowances (ex. Universal Allowance per child), or minimum pension value throughout his years in power (Palmisano and Teubal, 2020).

In Brazil, the economic constraints were not as latent as in Argentina. In midst of the political turmoil the country lived in 2015-2016, with Operation Carwash and impeachment process of President Rousseff, its GDP decreased by 3,8%. Besides the recession, the country struggled with an inflation rate of 10,7%, the highest since 2003 (TCU, 2015). Temer’s remedy passed through a recessive adjustment that put an end to neo-developmentalist experiment, which had already been reverted by Rousseff’s strict fiscal policy in her short second term as way to avoid a larger crisis. In the financial dimension, his administration rigidly sought to maintain the macroeconomic tripod. Nonetheless, his lack of legitimacy and popularity impeded him from deepening structural liberal-oriented reforms (Barbosa-Filho, 2020), but two reforms of his government were very relevant to alter the productive and social dimensions of the Brazilian development model. On the one hand, the government successfully approved a labor reform that loosened the Brazilian labor code, de-bureaucratizing the layoff processes and establishing temporary contracts. On the other, to give the market a proof of efficient management of the public expenditure and enforce legal limits for fiscal responsibility, Temer’s administration could install a constitutional amendment that froze all the public expenditure for ten years, which could be adjusted by annual inflation rates. Given the restrictive fiscal scenario, public investment plans were limited, and industrial policies were not on the agenda anymore.

With the reorientation of Brazilian and Argentinian development models, both new governments also introduced a new paradigm of insertion strategy. Both established insertion strategies that had a clear globalist profile, longing to acquiesce to globalization as it was seen as an opportunity that was completely neglected by previous governments. Part of it was investing most of diplomatic efforts towards traditional western partners, such as the US and the EU – without ignoring China economic relevance. In this sense, trade negotiations were the focus of the new governments’ diplomatic agenda and consequently, Mercosur’s negotiations with other external partners started to be multiplied. From 2016 to 2019, the Southern bloc-initiated talks with highly industrialized blocs and countries that could be a perfect destination for its primary goods exports, such as EFTA, South Korea, Singapore, and Canada. During the pink tide governments, Mercosur’s focused less on trade agreements, but when it did, it was mostly with developing countries, whose production could not menace Brazil and Argentina’s industrial efforts – for instance, the FTAs with Egypt (2010) or Palestine (2011) or complementary trade agreements with India (2005) or SACU (2008).

In any case, in the case of the Mercosur-EU negotiations, the globalist approach of the bloc’s leading member was clearly proved by an intensification of the negotiation process to form a bi-regional agreement as soon as possible.

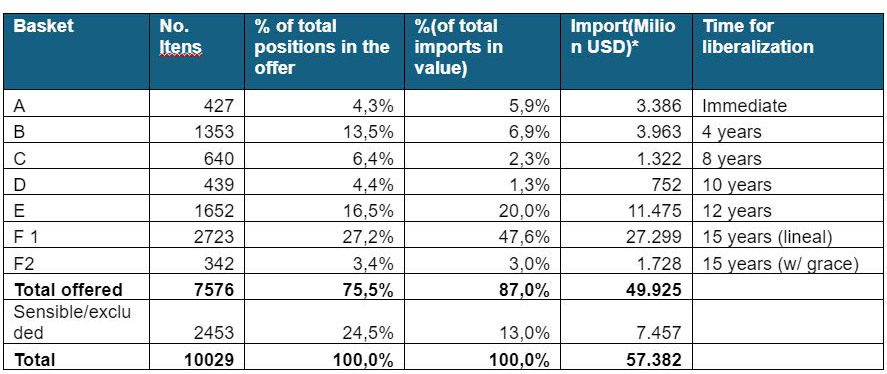

In May 2016, the first offers since 2004 presented were substantial and careful simultaneously. While Mercosur offer only attained 75,5% of the total tariff lines it imported from the EU, in terms of value, the liberalization offer indeed reached the 87% mark. This implied that while less items in absolute figures would be liberalized, more items with substantial trade value would fall into the width of the offer – see chart below. The liberalization would be carried out in six baskets and the whole liberalization would occur in fifteen years – with no fixed preference regime or quota regime but with grace years for products in the last basket. The EU offer represented 93,3% of imports from Mercosur in terms of value, but it disappointed the Southern bloc’s governments as they did not present the quotas for ethanol, meat, tobacco and other agricultural products (BID-INTAL, 2016).

Even so, driven by the insertion strategy of its major countries, Mercosur was ready to continue the negotiations and give them an institutional push. After the 26th BNC meeting in 2016, the first since 2012, Mercosur and the EU agreed to intensify the talks and even created intersectional meetings to evaluate the previous and next BNC encounters

Table 3. Mercosur’s liberalization offer (May 2016)

- Source: BID-INTAL (2016)

Indeed, 2017-2018 the 2017-2018 biennium was by far the busiest in the twenty years of the negotiations. In total, there were 17 meetings 11 BNC (from the 27th to 37th), 3 intersectional (in 2017), and 3 ministerial-level meetings (in December 2017, July 2018, and November 2018). The rhythm of the BNC encounters was particularly impressive, with 5 in 2017 and 6 in 2018. Before 2017-2018, the maximum number of BNC meetings was just 4 a year – in 2004, 2010, and 2011 (Ferro, 2024).

This remarkable negotiation pace allowed the bloc to exchange offers once again November-December 2017. On Mercosur’s side, Brazil and Argentina longed to a conclusion of the trade pillar as quick as possible. While the Brazilian government wanted to show positive results of the new international strategy, Macri wanted to guarantee a final en beauté for the negotiations with the signature of an FTA with on the margins of the WTO (Simonoff, 2020) – which would be held in Buenos Aires in December 2017. Nonetheless, the end of the negotiations was so close, but yet so far. The offers exchanged at the 31st BNC (November 28th-December 9th) frustrated both sides as the Europeans were not happy with the fifteen-year deadline for some manufactured goods (namely, vehicles) and Mercosur’s parties were frustrated by the new quota offers on meat and ethanol (OESP 12/11/2017). Not even the Ministerial-level meeting on the margins of the WTO round in Buenos Aires could reach a settlement.

In 2018, both sides tried to accelerate negotiations even more. The first three BNC meetings of the year tried to solve the contentious themes. A ministerial level took place on July 19th to try to solve the controversies, but they could not find a resolution that pleased both sides for: a. quotas for agricultural goods and its administration; b. liberalization calendar for cars; c. the extension of government procurements; d. in terms of intellectual property, the EU’s regime of geographic indication (BID-INTAL, 2018). Indeed, it was reported that Mercosur could cede in terms of EU’s geographic indications for a better offer (OESP 07/19/2018) – which would be a historical shift as especially Brazil and Argentina had always been against such commitment since the beginning of the negotiations. In any case, even after three more BNC meetings and a ministerial meeting before the G20 Summit in Buenos Aires, by end of that year, no agreement was reached. Brazilian chancellor, Aloysio Nunes, nonetheless, in an article/letter to end his term in office, argued that 12 out of 15 chapters were already negotiated and that “in terms of numbers” the deal was settled (Nunes, 2018).

At first, the election of Jair Bolsonaro (2019-2022) in Brazil made a possible conclusion slightly more uncertain due to his doubtful rhetoric regarding environmental preservation and his chosen chancellor. Nonetheless, it seems at least his first six months in office did not alter the course of the negotiations. One more BNC meeting, in March 2019, was required though. Finally, on June 29th, at the G20 Osaka Summit, the agreement in principle was announced by both parties.

It is interesting to notice that the combination of liberal development and globalist insertion strategy in Mercosur powerhouses led to an agreement in which they surrendered in most of their historical demands. More broadly, the strategy of using the “asymmetric reciprocity”/ “special and differential treatment” premise as a negotiation principle and the demands associated to it were loosened to reach the agreement. Indeed, the only requirement related to the special and differential treatment – a historic plead on Mercosur’s side since the beginning of the first round of negotiations – maintained in the agreement in principle was the different liberalization calendars between the EU and Mercosur, considering their economic imbalances.

Nonetheless, in all the other demands related to the SDT principle, Mercosur tended to cede. Firstly, it is important to mention Mercosur’s surrender in terms of market access. Defensively, it ceded on the width of the liberalization. The EU historically demanded an offer that ideally achieved the 90% margin, which was not attended by Mercosur in 2004 (at least in terms of value) and was not aimed by the bloc in the re-launch of the negotiations in 2010 – the bloc then only envisaged a 87% import liberalization. According to the text of the agreement in principle, the Southern bloc would liberalize 91% of its EU imports both in tariff lines and in value.

Offensively, in terms of agricultural goods, the quotas of the agreement in principle were generally too low – compared to the bloc’s exporting potential, the quotas offered by the EU in 2004, or Mercosur’s 2004 demand (Ferro, 2024). Also, according to the agreement in principle, contrary to Mercosur’s historical posture, the control of the quotas is the responsibility of the importer, and an in-quota tariff was maintained by some items such as meat, ethanol, and pigmeat (EU & Mercosur 2019). Finally, a longstanding requirement by Mercosur, the infant industry clause, which was even discussed even under the governments of Macri, Temer, and Bolsonaro (BNC, 2016, 2019) in the trade of goods chapter did not appear in the final text.

In terms of the SBS chapter, the concession was also very important and abandoned with Mercosur’s enduring demand of mutual recognition of sanitary certificates being abandoned. The text of the agreement in principle is clear in this sense, requiring “Mercosur countries to apply the same requirements to the entire territory of the EU, i.e. pragmatically applying the ‘EU as a single entity’ concept” (EU & Mercosur, 2019a, p. 7)

Without immediate industrial ambitions and trying to be integrated into the globalized world by their comparative advantages, Brazil and Argentina surrendered on themes that were very controversial in other negotiation phases since they could withdraw national sovereignty to foster industrialization (Ferro, 2024). First, via the agreement in principle, they accepted the EU’s property rights regime of geographic indication, under which they could no longer produce alimentary products that were specific to some European regions. Most importantly, Mercosur accepted the EU’s offensive interest in government procurement. Even though no Mercosur member state was a part of the WTO’s Government Procurement Agreement (2012), they accepted very similar conditions under the government procurement chapter of the agreement in principle. Therefore, using public procurement directly as industrial policy would be no longer possible given the agreement’s norms. The agreement gives “national treatment” for EU companies that want to provide goods, services and public works in any procuring process on the national level in Mercosur’s territory. In other words, the “national treatment” means that Mercosur’s countries would provide “treatment no less favorable than the treatment accorded to its own goods, services and suppliers” or “treat a locally established supplier less favorably than another locally established supplier on the basis of degree of foreign affiliation to, or ownership by, juridical or natural persons of the other Party” (EU & Mercosur, 2019b).

CONCLUSIONS

The agreement in principle reached in 2019 was the achievement of a new process of negotiation, which began with its relaunch in 2010. Although the confirmation of the negotiations’ success relies on the signature of the 2019 text and its subsequent ratification – recently threatened mostly on the European side –, reaching a common text for the trade pillar of the association agreement between the EU and Mercosur was already an undeniable progress.

This progress, nonetheless, is mainly due to the realignment of Brazil and Argentina under the sign of liberalism from 2016 to 2019. This manifested not only in their governments’ rhetoric or ideological preferences but also in their development model and international insertion strategies. This move made Mercosur press the UE even more towards a trade agreement and – most importantly – opened more bargaining space on the South American bloc’s side to make a common commercial agreement possible. Although the negotiations were resumed by the Brazilian and Argentinian governments of the first half of the 2010s, none of them was willing to cede on decisive topics for the EU – such as government procurement – for avoiding the loss of policy space to implement their industrialist agenda.

In other words, in this article, we can see that the relaunch of trade talks between the EU and Mercosur, shaped by the stances of South American leaders regarding a potential trade agreement, can be divided into two distinct phases with contrasting characteristics. From 2010 to 2015, although the negotiations had been formally relaunched, the administrations of Presidents Rousseff and Fernández de Kirchner, while placing differing degrees of importance on EU trade talks, shared a firm resistance to concessions that might limit their industrial policy space (e.g., intellectual property and public procurement). At the same time, they consistently insisted on differential and special treatment measures (such as more gradual liberalization for Mercosur, control of export quotas, increased agricultural quotas to reflect Mercosur’s export potential, and an infant industry clause, among other stipulations detailed in section 2 of this article). Between 2016 and 2019, however, the administrations of Presidents Temer, Macri, and later Bolsonaro, assigned significant importance to the agreement and made an unprecedented departure from the prior governments' positions regarding demands for differential treatment—reflecting a shift in their development models and international integration strategies. This shift ultimately led to the landmark achievement of the 2019 agreement in principle, marking the end of the negotiation phase in the EU-Mercosur trade talks.

NOTES

1 Shortened and reviewed version of the last chapter of master’s dissertation entitled The Mercosur-EU agreement: an approach based on foreign policy and development models of Brazil and Argentina (1995-2019); see Ferro (2024).

2 From here on, FSP stands for Folha de São Paulo and is referenced with the bibliography.

3 Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership was trade agreement negotiated between the US and the EU.

4 Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership is the largest trade bloc in the world. It was signed in 2020 by Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

5 From here on, the newspaper O Estado de Sao Paulo referenced as OESP

6 Brazilian Chancellor Antonio Patriota (2011-2015) had already hinted the possibility of a negotiation with the EU at different speeds for each of Mercosur member states in August 2013 in an interview with Financial Times. EU’s Commissioner for Trade, Karel de Gucht (2009-2014), said the EU was open for national negotiations. On a public communiqué, the Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs later denied that negotiations without the other Mercosur member states could be possible (OESP 08/12/2013).

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

Actis, E., Lorenzini, M. E., & Zelicovich, J. (2016). Modelo de desarrollo y estrategia de inserción: claves para la interpretación de su relación. In: Modelos de Desarrollo e Inserción Internacional. Aportes para el análisis de la política exterior argentina desde la redemocratización 1983-2011, 15-30.

Actis, E., Lorenzini, M. E., & Zelicovich, J. (2017). La vinculación entre modelo de desarrollo y estrategia de inserción en la Argentina democrática (1983-2011). Studia Politicae, (41), 105-135.

Álvarez, M. V., & Zelicovich, J. (2020). El acuerdo MERCOSUR-Unión Europea: un abordaje multicausal de la conclusión del proceso negociador. Relaciones Internacionales, nº 44, pp. 107-125.

Arana, A G.. (2017) The European Union’s policy towards Mercosur: responsive not strategic. Manchester: Manchester University Press

Araújo, R. G. (2018) O jogo estratégico nas negociações Mercosul-União Europeia. Brasilia: FUNAG

Belini, C., & Korol, J. C. (2020). Historia económica de la Argentina en los siglos XX y XXI. Siglo XXI Editores.

Berringer, T., & Forlini, L. (2018). Crise política e mudança na política externa no governo Temer: contradições no seio da burguesia interna brasileira. In: Conjuntura Austral, 9(48), 5-19.

BID-INTAL (2005). Informe MERCOSUR No. 10 (2004-2005). INTAL https://doi.org/10.18235/0009523

________ (2011). Informe MERCOSUR No. 16 (2010-2011). INTAL http://dx.doi.org/10.18235/0009885

________ (2013). Informe MERCOSUR No. 18 (2012-2013) Segundo Semestre 2012 - Primer Semestre 2013. INTAL http://dx.doi.org/10.18235/0010703

________. (2016). Informe MERCOSUR No 21 (2015-2016) Segundo semestre 2015 - Primer semestre 2016. INTAL http://dx.doi.org/10.18235/0010132

________. (2018). Informe Mercosur: hacia um cambio necesario. INTAL. http://dx.doi.org/10.18235/0001732

Bi-regional Negotiations Committee (2016). Report of the XXVI negotiation round on the trade part of the EU-Mercosur Association Agreement. Retrieved from https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/09242a36-a438-40fd-a7af-fe32e36cbd0e/library/8aca42c4-fb01-47a9-a47d-e4de2ff6a23d/details

____________________________. (2019). Report of the XXXVIII negotiation round on the trade part of the EU-Mercosur Association Agreement. Retrieved from https://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/09242a36-a438-40fd-a7af-fe32e36cbd0e/library/52d81fe2-bac0-4bfe-bdbd-2fe78c764b7e/details

European Union & Mercosur. (2019a). Agreement in principle of the EU-Mercosur trade agreement. Retrieved from: https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/mercosur/eu-mercosur-agreement_en

______________________. (2019b). Chapter of Government procurement: Agreement in principle of the EU-Mercosur trade agreement. Retrieved from: https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/mercosur/eu-mercosur-agreement_en.

Brazil and European Union. (2009). Third European Union-Brazil Summit Joint Statement. Retrieved from: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/er/110440.pdf

_______________________. (2010). Fourth European Union-Brazil Summit Joint Statement. Retrieved from: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/er/115812.pdf

Bresser-Pereira, L. C. (2013). O governo Dilma frente ao" tripé macroeconômico" e à direita liberal e dependente. Novos estudos CEBRAP, 5-15.

Bresser-Pereira, L. C. (2018). Em busca do Desenvolvimento perdido. Rio de Janeiro: Editora da FGV.

Cervo, A. L., & Lessa, A. C. (2014). O declínio: inserção internacional do Brasil (2011-2014). Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, 57, 133-151.

Eonomic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). (2018). Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean 2018 – Argentina. Retrieved August 15, 2024, from https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/4c0a7d2c-ffba-44f8-90ea-34c5bc8de852/content

Escudé, C. (1995). El realismo de los estados débiles: la política exterior del primer gobierno Menem frente a la teoría de las relaciones internacionales. Buenos Aires: Grupo Editor Latinoamericano.

Ferro. J. V. (2024) The EU-Mercosur trade negotiations: Foreign policy and development models in Brazil and Argentina (1995-2019). Master’s Dissertation in Latin American Studies – Stockholm University.

Filho, R. C. (2018). “ As negociações Mercosul-União Europeia a partir de 2009”. In: Araújo, R. G. O jogo estratégico nas negociações Mercosul-União Europeia. Brasilia: FUNAG

Frenkel, A., & Azzi, D. (2018). Cambio y ajuste: la política exterior de Argentina y Brasil en un mundo en transición (2015-2017). Colombia internacional, (96), 177-207.

Folha de São Paulo. (July 31st, 2009). Brasil desistiu da Rodada de Doha, sinaliza Amorim”.

________________. (October 5th, 2009). Cúpula retomará acordo EU-Mercosul.

IMF. (2024). Financial transactions with Brazil. Retrieved August 5, 2024, from https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/tad/extrans1.aspx?memberKey1=90&endDate=2099-12-31&finposition_flag=YES

Massot, J. M. (2019). La política cambiaria argentina entre 2016 y 2019. Situación y alternativas desde una perspectiva de Economía Política. Actualidad Económica, 29(99), 3-16.

Nunes, A. (2018). “As negociações Mercosul-União Europeia”. O Estado de São Paulo December 28th

O Estado de São Paulo. (November 10th 2013) Caracas está fora de acordo Mercosul-UE.

_________________. (Feburary 26th 2014). Brasil, UE e Mercosul atolado.

_________________. (May 1st 2014). Acordo entre Mercsoul e UE está ameaçado.

_________________. (May 28th 2014). Acordo comercial entre UE e Mercosul ‘patina’.

_________________. (December 11th 2017). Acordo entre Mercosul e UE é adiado de novo.

_________________. (July 19th 2018). Encontro entre Mercosul e UE fica sem acordo.

Palmisano, T., & Teubal, M. (2020). Aspectos generales de la política económica del gobierno de Mauricio Macri en Argentina (2015-2018). In: Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 11(37), 165-187. Disponible en RIDAA-UNQ Repositorio Institucional Digital de Acceso Abierto de la Universidad Nacional de Quilmes http://ridaa.unq.edu.ar/handle/20.500.11807/355

Pose, N. (2022). La política de las preferencias de la industria en Brasil y Argentina sobre la agenda de acuerdos de comercio preferencial de Mercosur. Intereses (PhD Thesis). Montevideo: Udelar. FCS.

Rapoport, M. (2017). Política internacional argentina. Buenos Aires: Capital Intelectual.

Rodríguez, J. D., & Sanahúja, J. A. Veinte años de negociaciones Unión Europea-Mercosur: Del interregionalismo a la crisis de la globalización. Documentos de Trabajo nº 13 (2ª época), Madrid, Fundación Carolina.

Salgado, V. T., & Bressan, R. N. (2020). O acordo de associação Mercosul-União Europeia e a política externa brasileira. Revista Neiba, Cadernos Argentina Brasil, 9(1).

Savini, M. (2001). As negociações comerciais entre Mercosul e União Européia. Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, 44, 109-125.

Santos, L. B. dos. (2018). As negociações do acordo de associação inter-regional Mercosul e União Europeia: o posicionamento dos grupos agrícolas e industriais de Argentina e Brasil (Master’s Thesis). San Tiago Dantas, São Paulo.

Simonoff, A. (2020). Acuerdos Mercosur-Unión Europea desde la perspectiva de la política exterior Argentina. Íconos. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 68, 57-73

Soares de Lima, M. R. (2000). Instituições democráticas e política exterior. Contexto Internacional, 22(2), 265.

TCU – Tribunal de Contas da União (2016). Desempenho da Economia Brasileira em 2015. Retrieved from https://sites.tcu.gov.br/contas-do-governo-2015/3_Desempenho%20da%20Economia%20Brasileira_FINAL.pdf

Ventura, D. D. F. L. (2003). As assimetrias entre o Mercosul e a União Europeia: os desafios de uma associação inter-regional. Editora Manole Ltda.

World Bank. (2024). Total reserves (includes gold, current US$) - Brazil. Retrieved August 15, 2024, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/FI.RES.TOTL.DT.ZS?locations=BR

Wylde, C. (2016). Post-neoliberal developmental regimes in Latin America: Argentina under Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner. New political economy, 21(3), 322-341.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest related to the article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Not applicable.

FUNDING

Not applicable.

PREPRINT

Not published.

COPYRIGHT

Copyright is held by the authors, who grant the Revista Política Internacional the exclusive rights of first publication. Authors may establish additional agreements for the non-exclusive distribution of the version of the work published in this journal (e.g., publication in an institutional repository, on a personal website, publication of a translation or as a book chapter), with the acknowledgment of having been first published in this journal. Regarding copyright, the journal does not charge any fee for submission, processing or publication of articles.